Each year, I publish the books I read with a bit of commentary. The goal is to encourage myself and others to read good books and to share ideas. This year I broke down what I read in a different way and learned I probably need to be reading more books written by people who are less like myself, as well as books published longer ago.

This Year in Data about Books

With my growing fascination with data, I played around with my reading list seemed like a fun data set. No-one else in the world has this data set. To be fair, no-one else cares. I was curious to see what questions I might be able to ask of my personal data set. In some ways it’s a step on the quantified life path, where people record information about their lives to glean meaningful insights. Smartphones count our steps to help us understand whether we’re moving enough, for example. My reading log lead to some interesting ideas.

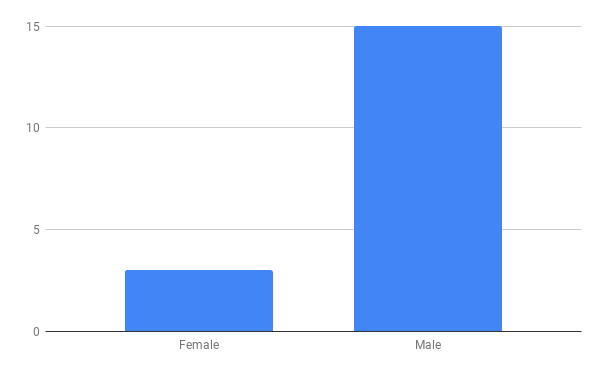

I don’t read as many books written by women

Of the 18 books I read in 2019, only 3 were written by women. This is not terribly surprising since book-writing and publication has been a historically male dominated industry. Even so, the breakdown surprised me and made me a little sad. A sneak preview of the list from 2020 wasn’t much better when I looked. Myself, and likely many others, are missing out on insightful thoughts, opinions, and perspectives. The world would probably be better off if we read more books by people who were less like ourselves.

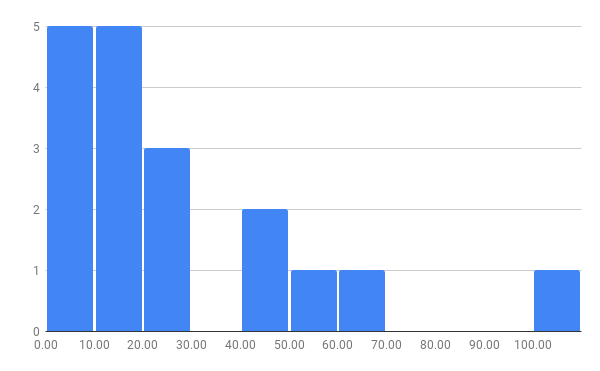

Most of the books I read were published fairly recently.

Books have been around for millennia, and yet most of what I read has been published in my lifetime. The histogram below shows the the number of years between when a book was published, and when I read it distributed in 10-year buckets. 13 of 18 books I read in 2019 were published after 1990. Similarly to the point above, I’m probably missing out on ideas and wisdom from people who are less like me.

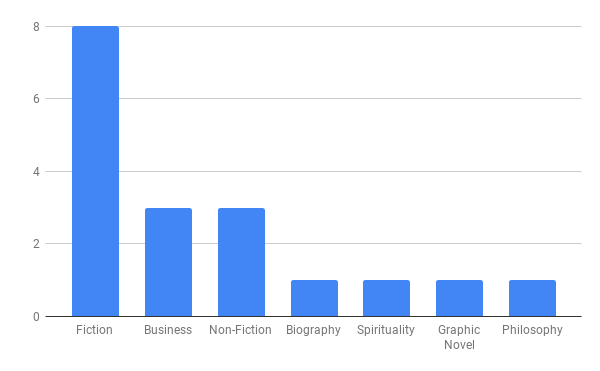

I still love fiction

Years ago, I wrote a blog on Medium about the importance of reading fiction. Unfortunately, after 6 years, I can no longer find it, but the moral of the story was that people need to read more fiction. Many friends and colleagues argue reading non-fiction or the latest business book is more insightful, they learn more from those genres. I believe all books help us understand, interpret, and reason about the world. Fictions method for teaching us uses different parts of our brains, but that doesn’t make the lessons any less valuable.

2019 Books List

Author |

Title |

Rating |

| Asimov, Isaac | I, Robot | 7.2 |

| Atwood, Margaret | Oryx and Crake | 7.8 |

| Brooks, Frederick | The Mythical Man-Month | 8 |

| Browder, Bill | Red Notice: A True Story of High Finance, Murder, and One Man’s Fight for Justice | 7.4 |

| Carpenter, Humphrey | J.R.R. Tolkein: A Biography | 6.2 |

| Crichton, Michael | Jurassic Park | 7.1 |

| Crichton, Michael | The Lost World | 7.6 |

| Dalai Lama XIV | Four Noble Truths | 4.8 |

| Dick, Phillip K. | The Game Players of Titan | 8.8 |

| Doxiadis, Apostolos | Logicomix: An Epic Search for Truth | 9 |

| Francesca, Lisa | The Wedding Officiant’s Guide | 9 |

| Gaiman, Neil | Fragile Things | 5.6 |

| Greer, Adam | Less | 6 |

| Orleans, Susuan | The Library Book | 8 |

| Rogoff, Keneth | The Curse of Cash | 9 |

| Russel, Bertrand | The Problems of Philosophy | 8.2 |

| Verghese, Abraham | Cutting For Stone | 8.2 |

| Voss, Chris | Never Split the Difference | 7.8 |

Logicomix by Apostolos Doxiadis

The first graphic novel I’ve ever read. Fantastic. All about the life of Bertrand Russell, an expert weaving of history, biography, philosophy, and math. By far the most enjoyable read of the year and got me into the genre. If you thought of graphic novels only as long comic books, like I did, pick this one up.

The Curse of Cash by Keneth Rogoff

This was one of the optional books on the syllabus as part of an economics class in my MBA program. Rogoff argues we should work towards the elimination of high-denomination bills in the United States. His arguments range from simple to complex. The simplest: when was the last time you needed to use a $100? How big of an inconvenience would using five $20s instead have been? The average person does not need such large bills. Who likes large bills? Criminals. People who want to avoid paying taxes by working outside of the banking system. People who want to transport or hide lots of illegal money. It is much easier to hide $1M when it is in one duffle bag instead of 5. He declares almost 80% of cash in circulation is made up of $100 bills, or roughly $4,200 per person. He fairly points out this is a bit fishy. Who has all these bills if the average person doesn’t have them and isn’t using them? They don’t seem to be necessary for most economic transactions in a modern economy.

The complex: it ties the hands of the Fed with regards to interest rates. There is no zero bound in mathematics. Negative numbers are extremely useful. Negative interest rates might also be useful. If it cost people and businesses to store their money in banks, they would be less inclined to keep it there and would instead spend. This could be a useful tool in some economic scenarios. We’ve seen the Fed resort to more heavy-handed quantitative easing tools in recent years. But cash gets in the way. People and businesses have the option to convert their wealth to cash instead of keeping it in the bank, avoiding negative interest rates.